What Factor Might Influence Family Composition? Religious Beliefs Poverty War All of the Above

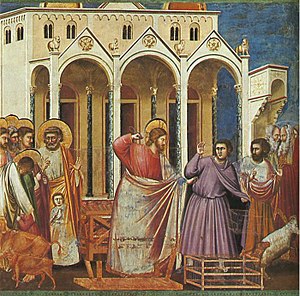

Jesus casting out the money changers from the Temple by Giotto, 14th century

At that place have been a multifariousness of Christian views on poverty and wealth. At one stop of the spectrum is a view which casts wealth and materialism as an evil to be avoided and even combated. At the other stop is a view which casts prosperity and well-being as a blessing from God.

Many taking the one-time position address the topic in relation to the modernistic neoliberal capitalism that shapes the Western earth. American theologian John B. Cobb has argued that the "economism that rules the West and through it much of the East" is directly opposed to traditional Christian doctrine. Cobb invokes the educational activity of Jesus that "man cannot serve both God and Mammon (wealth)". He asserts that it is obvious that "Western society is organized in the service of wealth" and thus wealth has triumphed over God in the West.[1] Scottish theologian Jack Mahoney has characterized the sayings of Jesus in Mark ten:23–27 as having "imprinted themselves so deeply on the Christian community through the centuries that those who are well off, or even comfortably off, oftentimes feel uneasy and troubled in conscience."[2]

Some Christians argue that a proper understanding of Christian teachings on wealth and poverty needs to accept a larger view where the accumulation of wealth is not the primal focus of one's life but rather a resource to foster the "good life".[3] Professor David Due west. Miller has constructed a three-part rubric which presents three prevalent attitudes among Protestants towards wealth. According to this rubric, Protestants have variously viewed wealth as: (1) an law-breaking to the Christian faith (2) an obstacle to faith and (3) the outcome of organized religion.[iv]

Wealth and organized religion [edit]

Wealth as an offense to faith [edit]

According to historian Alan South. Kahan, in that location is a strand of Christianity that views the wealthy man every bit "especially sinful". In this strand of Christianity, Kahan asserts, the day of judgment is viewed as a time when "the social order will be turned upside down and ... the poor will turn out to exist the ones truly blessed."[5]

David Miller suggests that this view is similar to that of the third century Manicheans who saw the spiritual earth every bit being good and the textile world as evil with the two being in irreconcilable conflict with each other.[4] Thus, this strand of Christianity exhorts Christians to renounce material and worldly pleasures in club to follow Jesus. As an example, Miller cites Jesus' injunction to his disciples to "take nothing for the journeying."Marking half-dozen:8–nine

Wealth as an obstacle to faith [edit]

Co-ordinate to David Miller, Martin Luther viewed Mammon (or the desire for wealth) every bit "the near common idol on earth". Miller cites Jesus' run into with the rich ruler Mark 10:17–31 as an case of wealth being an obstacle to religion. Co-ordinate to Miller, it is non the rich man'due south wealth per se that is the obstacle only rather the man'south reluctance to give up that wealth in guild to follow Jesus. Miller cites Paul'due south observation in 1st Timothy that, "people who want to get rich fall into temptation and a trap and into many foolish and harmful desires that plunge men into ruin and destruction." (i Timothy 6:9) Paul continues on with the ascertainment that "the dearest of coin is the root of all evil." (1 Timothy half-dozen:10) Miller emphasizes that "it is the love of money that is the obstacle to faith, non the money itself."[4]

Jesus looked effectually and said to his disciples, "How hard it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God!" The disciples were amazed at his words. But Jesus said again, "Children, how hard it is to enter the kingdom of God! It is easier for a camel to get through the centre of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God." (Marker x:23–25)

Kahan cites Jesus' injunction against amassing material wealth equally an example that the "good [Christian] life was one of poverty and charity, storing up treasures in heaven instead of earth.[5]

Do non store up for yourselves treasures on globe, where moth and rust destroy, and where thieves break in and steal. But store upward for yourselves treasures in heaven, where moth and rust do non destroy, and where thieves do not break in and steal. For where your treasure is, there your center will be also. (Matthew 6:19–21)

Jesus counsels his followers to remove from their lives those things which cause them to sin, saying "If your paw causes you to sin, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life maimed than to go with ii hands into hell, where the fire never goes out." Mark ix:42–49. In order to remove the want for wealth and material possessions as an obstruction to faith, some Christians have taken vows of poverty. Christianity has a long tradition of voluntary poverty which is manifested in the form of divineness, clemency and almsgiving.[6] Kahan argues that Christianity is unique because it sparked the get-go of a phenomenon which he calls the "Great Renunciation" in which "millions of people would renounce sex and money in God'due south name."[v]

Thomas Aquinas wrote "Greed is a sin against God, just equally all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things."[ citation needed ]

In Roman Catholicism, poverty is one of the evangelical counsels. Pope Benedict Xvi distinguishes "poverty chosen" (the poverty of spirit proposed by Jesus), and "poverty to be fought" (unjust and imposed poverty). He considers that the moderation implied in the former favors solidarity, and is a necessary condition and so every bit to fight effectively to eradicate the corruption of the latter.[vii] Certain religious institutes and societies of Apostolic life also take a vow of extreme poverty. For case, the Franciscan orders take traditionally foregone all individual and corporate forms of ownership; in another example, the Catholic Worker Movement advocates voluntary poverty.[8] [9] Christians, such as New Monastics, may choose to reject personal wealth and follow an ascetic lifestyle, in role as a protestation confronting "a church and public that embraces wealth, luxury and ostentatious ability."[x]

Wealth as an outcome of organized religion [edit]

One line of Protestant thinking views the pursuit of wealth equally not only acceptable only as a religious calling or duty. This perspective is generally ascribed to Calvinist and Puritan theologies, which view hard work and frugal lifestyles as spiritual acts in themselves. John Wesley was a strong proponent of gaining wealth, according to his famous "Sermon l," in which he said, "gain all you can, save all you tin can and give all y'all can."[4] Information technology is impossible to give to charity if ane is poor; John Wesley and his Methodists were noted for their consistently large contributions to clemency in the grade of churches, hospitals and schools.

Included among those who view wealth every bit an consequence of religion are modern-day preachers and authors who propound prosperity theology, teaching that God promises wealth and affluence to those who will believe in him and follow his laws. Prosperity theology (likewise known as the "wellness and wealth gospel") is a Christian religious conventionalities whose proponents claim the Bible teaches that fiscal blessing is the will of God for Christians. Most teachers of prosperity theology maintain that a combination of religion, positive speech, and donations to specific Christian ministries volition ever cause an increase in fabric wealth for those who do these actions. Prosperity theology is almost e'er taught in conjunction with continuationism.

Prosperity theology first came to prominence in the United States during the Healing Revivals in the 1950s. Some commentators have linked the genesis of prosperity theology with the influence of the New Thought movement. It later figured prominently in the Give-and-take of Organized religion move and 1980s televangelism. In the 1990s and 2000s, it became accepted by many influential leaders in the charismatic movement and has been promoted by Christian missionaries throughout the globe. It has been harshly criticized past leaders of mainstream evangelicalism as a non-scriptural doctrine or equally an outright heresy.

Precursors to Christianity [edit]

Professor Cosimo Perrotta describes the early Christian period equally one which saw "the meeting and clash of iii great cultures: the Classical, the Hebrew (of the Former Testament) and the Christian." Perrotta describes the cultures equally having radically dissimilar views of money and wealth. Whereas the Hebrew civilisation prized fabric wealth, the Classical and Christian cultures either held them in contempt or preached indifference to them. Nevertheless, Perrotta points out that the motivation of the Classical and Christian cultures for their attitudes were very different and thus the logical implications of the attitudes resulted in dissimilar outcomes.[11]

Jewish attitudes in the Erstwhile Testament [edit]

Perrotta characterizes the attitude of the Jews as expressed in the Old Testament scriptures every bit being "completely different from the classical view." He points out that servile and hired piece of work was not scorned by the Jews of the One-time Attestation as it was by Greco-Roman thinkers. Instead, such work was protected by biblical commandments to pay workers on time and not to cheat them. The poor were protected from being exploited when in debt. Perrotta asserts that the goal of these commandments was "not simply to protect the poor but also to foreclose the excessive accumulation of wealth in a few hands." In essence, the poor man is "protected by God". Even so, Perrotta points out that poverty is non admired nor is information technology considered a positive value by the writers of the Sometime Testament. The poor are protected because the weak should be protected from exploitation.[12]

Perrotta points out that textile wealth is highly valued in the Old Testament; the Hebrews seek information technology and God promises to bless them with it if they will follow his commandments.[12] Joseph Francis Kelly writes that biblical writers get out no doubt that God enabled men such as Abraham, Isaac, Jacob and Solomon to attain wealth and that this wealth was a sign of divine favor. However, Kelly also points out that the Old Testament insisted that the rich aid the poor. Prophets such as Amos castigated the rich for oppressing the poor and crushing the needy. In summary, Kelly writes that, "the Sometime Attestation saw wealth equally something good but warned the wealthy not to use their position to harm those with less. The rich had an obligation to alleviate the sufferings of the poor."[13]

New Testament [edit]

Blessed are y'all who are poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.

The Gospels [edit]

Jesus explicitly condemns excessive honey of wealth as an intrinsic evil in various passages in the Gospels, especially in Luke (Luke 16:10–fifteen being an especially articulate example). He too consistently warns of the danger of riches as a hindrance to favor with God; every bit in the Parable of the Sower, where it is said:

- "And the cares of this earth, and the deceitfulness of riches, and the lusts of other things entering in; it chokes the Discussion, which becomes unfruitful"-Marking four:19

Jesus makes Mammon a personification of riches, one in opposition to God, and which claims a person's service and loyalty as God does. But Jesus rejects the possibility of dual service on our function: for, he says, no one tin serve both God and Mammon.

In the story of Jesus and the rich fellow the young ruler'southward wealth inhibits him from post-obit Jesus and thereby attaining the Kingdom. Jesus comments on the young man'south discouragement thus:

- "How difficult it is for the rich to enter the kingdom of God! Indeed, it is easier for a camel to go through the centre of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God." Those who heard this were astonished, "Who then can exist saved?", they asked. Jesus replied, "What is impossible with human is possible with God."-Matthew 19:23–27

In the Sermon on the Mount and the Sermon on the Plain, Jesus exhorts his hearers to sell their earthly appurtenances and requite to the poor, and so provide themselves with "a treasure in heaven that volition never fail, where no thief comes well-nigh and no moth destroys" (Luke 12:33); and he adds "For where your treasure is, there volition your middle be as well." (Luke 12:34)

In The Parable of the Rich Fool Jesus tells the story of a rich man who decides to balance from all his labors, saying to himself:

- "And I will say to myself 'You have plenty of grain laid up for many years. Take life like shooting fish in a barrel; swallow, potable and be merry.' Merely God spoke to him, saying 'You fool! This very night your life will be required of you lot. And so who will get all that y'all have prepared for yourself?'" (Luke 12:16–20)

And Jesus adds, "This is how information technology volition be with whoever stores up things for themselves but is non rich toward God." (Luke 12:21)

Jesus and Zacchaeus (Luke 19:1–10) is an example of storing up heavenly treasure, and beingness rich toward God. The repentant revenue enhancement collector Zacchaeus non merely welcomes Jesus into his firm but joyfully promises to requite half of his possessions to the poor, and to rebate overpayments four times over if he defrauded anyone (Luke 19:viii).

Luke strongly ties the right use of riches to discipleship; and securing heavenly treasure is linked with caring for the poor, the naked and the hungry, for God is supposed to accept a special interest in the poor. This theme is consequent with God's protection and intendance of the poor in the Onetime Testament.

Thus, Jesus cites the words of the prophet Isaiah (Isaiah 61:1–2) in proclaiming his mission:

- "The Spirit of the Lord is upon Me, because He has anointed Me to preach the Gospel to the poor, to heal the brokenhearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovery of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are hobbling, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord." (Luke 4:18–19)

Luke, equally is well known, had a particular concern for the poor as the subjects of Jesus' compassion and ministry. In his version of the Beatitudes, the poor are blessed as the inheritors of God'south kingdom (Luke half dozen:xx–23), even as the corresponding curses are pronounced to the rich (Luke vi:24–26).

God's special interest in the poor is also expressed in the theme of the eschatological "nifty reversal" of fortunes between the rich and the poor in The Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55):

- He has shown the might of his arm:

- and has scattered the proud, in the conceit of their hearts.

- He has pulled downward the mighty from their thrones,

- and exalted the lowly.

- He has filled the hungry with good things;

- and the rich has sent empty away.

- —Luke one:51–53

and in Jesus' repeated use of the tag "many that are first shall be final, and the last shall be start" (Matthew 19:30, Matthew 20:sixteen, Mark 10:31, & Luke thirteen:30) and like figures (Matthew 23:12, Luke fourteen:11, & Luke 18:14).

In the Parable of the Hymeneals Feast, information technology is "the poor, the crippled, the bullheaded and the lame" who become God's honored guests, while others decline the invitation because of their earthly cares and possessions (Luke fourteen:7–14).

Acts of the Apostles [edit]

Luke's business organisation for the rich and the poor continues in Acts with a greater focus on the unity of the nascent Christian communities. The 2 famous passages (Acts two:43–45; Acts four:32–37), which accept been appealed to throughout history every bit the "normative platonic" of the community of goods for Christians, rather describe the extent of fellowship (koinōnia) in Jerusalem customs every bit a role of distinctive Christian identity. Acts besides portrays both positive and negative uses of wealth: those who practiced almsgiving and generosity to the poor (Acts 9:36; Acts 10:ii–4) and those who gave priority to money over the needs of others (Acts 5:1–eleven; Acts eight:14–24).

Epistles [edit]

For Paul, riches mainly denotes the character and activeness of God and Christ – spiritual blessings and/of salvation – (east.k., Romans 2:4; Romans 9:23; ii Corinthians 8:9; Ephesians i:7–eighteen; Ephesians 2:four–vii) although he occasionally refers to typical Jewish piety and Greco-Roman moral teachings of the time, such equally generosity (Romans 12:8–13; two Corinthians 8:2; Ephesians four:28; one Timothy 6:17) and hospitality (i Timothy v:x) with warnings confronting pride (1 Timothy 6:17) and greed (1 Corinthians 5:11; ane Timothy 3:8). 1 Timothy 6:10 seems to reverberate a popular Cynic-Stoic moral teaching of the period: "the love of money is a root of all kinds of evil." Paul'due south focus of generosity is devoted to the collection for the Church in Jerusalem (Gal. ii.ten; 1 Cor. xvi.1–4; two Cor 8.ane – 9.15; Rom. fifteen.25–31) as an of import symbol of unity between Jewish and gentile believers with an appeal to fabric and spiritual reciprocity. It is besides noteworthy that Paul's didactics in 1 Tim 6:17 implies in that location were rich believers in the Early Church.

A concept related to the accumulation of wealth is Worldliness, which is denounced past the Epistles of James and John: "Don't you know that friendship with the world is enmity with God? Therefore whoever wishes to be a friend of the earth makes himself an enemy of God" (Ja 4.iv). The first letter of John says, in a similar vein: "Do not love the earth or the things in the world. If anyone loves the world, the love of the Father is not in him" (1 Jn 2:fifteen).

The Epistle of James as well stands out for its vehement condemnation of the oppressive rich, who were presumably outsiders to the Christian community, which mainly consisted of the poor. Adopting the Psalter's convention of the "wicked rich" and the "pious poor" and adopting its voice, James indicts the rich with the sins of hoarding wealth, fraudulently withholding wages, corruption, pride, luxury, covetousness and murder; and denounces the folly of their actions in the face of the imminent Day of Judgement.

Revelation [edit]

Finally, the Revelation treats earthly riches and commercial activities with groovy ambivalence. While Jesus exposes the true poverty of the Laodicean church's boast of wealth (iii.17–18), he presents himself as the truthful source and dispenser of wealth (cf. 2 Cor. 8.xiii–15). Afterward, earthly riches and businesses activities are associated with the sins of Babylon, the earthly ability of evil with self-accorded celebrity and luxury, whose autumn is imminent (18.i–24). However, the Revelation likewise portrays the New Jerusalem with a lavish materialistic clarification, made of pure gold decorated with "every kind of jewel" (21.18–19).

Early on Christianity [edit]

15th-century fresco of the Apostles, Turin, Italy

Early Christianity appears to have adopted many of the upstanding themes found in the Hebrew Bible. However, the teachings of Jesus and his apostles equally presented in the New Testament exhibit an "acute sensitivity to the needs of the disadvantaged" that Frederick sees as "adding a critical edge to Christian teaching where wealth and the pursuit of economic gain are concerned.[14]

Alan Kahan points to the fact that Jesus was a poor man as emblematic of "a revolution in the way poverty and wealth were viewed."[15] This is not to say that Christian attitudes borrowed nothing from Christianity's Greco-Roman and Jewish precursors. Kahan acknowledges that, "Christian theology absorbed those Greco-Roman attitudes towards money that complemented its own." However, every bit Kahan puts it, "Never before had whatsoever god been conceived of as poor."[15] He characterizes Christian charity every bit beingness "dissimilar in kind from the generosity praised in the classical tradition."[16]

Kahan contrasts the attitudes of early Christians with those of classical thinkers such every bit Seneca. The New Testament urges Christians to sell material possessions and give the money to the poor. According to Kahan, the goal of Christian clemency is equality, a notion which is absent in the Greco-Roman attitudes toward the poor.[16]

Cosimo Perrotta characterizes the Christian attitude vis-a-vis poverty and work as being "much closer to the tradition of the Old Testament than to classical civilisation."[eleven] However, Irving Kristol suggests that Christianity's attitude towards wealth is markedly dissimilar from that of the Hebrews in the Erstwhile Testament. Kristol asserts that traditional Judaism has no precepts that parallel the Christian exclamation that information technology is hard for a rich man to get into heaven.[17]

Perrotta characterizes Christianity as non disdaining material wealth as did classical thinkers such as Socrates, the Cynics and Seneca and yet not desiring it as the Old Testament writers did.[12]

Patristic era [edit]

Many of the Church Fathers condemned individual property and advocated the communal ownership of property equally an ideal for Christians to follow. However, they believed early on that this was an ideal which was not very applied in everyday life and viewed individual property as a "necessary evil resulting from the fall of man."[18] American theologian Robert Grant noted that, while almost all of the Church Fathers condemn the "dear of money for its own sake and insist upon the positive duty of almsgiving", none of them seems to take advocated the full general application of Jesus' counsel to the rich young human being viz. to requite away all of his worldly possessions in order to follow him.[nineteen]

Augustine urged Christians to plough away from the desire for material wealth and success. He argued that the accumulation of wealth was non a worthy goal for Christians.

Although Clement of Alexandria counselled that property be used for the proficient of the public and the community, he sanctioned private ownership of property and the accumulation of wealth.[20] Lactantius wrote that "the ownership of belongings contains the textile of both vices and virtues merely communism [communitas] contains nothing but license for vice."[nineteen]

Medieval Europe [edit]

By the beginning of the medieval era, the Christian paternalist ethic was "thoroughly entrenched in the civilization of Western Europe." Individualist and materialist pursuits such as greed, forehandedness, and the accumulation of wealth were condemned equally un-Christian.[21]

Madeleine Gray describes the medieval system of social welfare as 1 that was "organized through the Church building and underpinned by ideas on the spiritual value of poverty.[22]

According to historian Alan Kahan, Christian theologians regularly condemned merchants. For example, he cites Honorius of Autun who wrote that merchants had piddling chance of going to heaven whereas farmers were likely to be saved. He farther cites Gratian who wrote that "the man who buys something in social club that he may gain by selling information technology again unchanged and equally he bought it, that man is of the buyers and sellers who are cast forth from God's temple."[23]

However, the medieval era saw a modify in the attitudes of Christians towards the accumulation of wealth. Thomas Aquinas divers avarice not just as a desire for wealth but equally an immoderate want for wealth. Aquinas wrote that it was acceptable to accept "external riches" to the extent that they were necessary for him to maintain his "condition of life". This argued that the dignity had a right to more wealth than the peasantry. What was unacceptable was for a person to seek to more wealth than was appropriate to one's station or aspire to a higher station in life.[15] The menstruum saw fierce debates on whether Christ owned property.

The Church building evolved into the single most powerful institution in medieval Europe, more than powerful than whatsoever single potentate. The Church was and then wealthy that, at in one case, it endemic as much as 20–30% of the land in Western Europe in an era when land was the chief grade of wealth. Over time, this wealth and power led to abuses and corruption.[ citation needed ]

Monasticism [edit]

As early every bit the 6th and 7th centuries, the issue of property and move of wealth in the event of outside aggression had been addressed in monastic communities via agreements such as the Consensoria Monachorum.[24] [25] By the eleventh century, Benedictine monasteries had become wealthy, owing to the generous donations of monarchs and nobility. Abbots of the larger monasteries accomplished international prominence. In reaction to this wealth and power, a reform motion arose which sought a simpler, more austere monastic life in which monks worked with their hands rather than interim as landlords over serfs.[26]

At the beginning of the 13th century, mendicant orders such as the Dominicans and the Franciscans departed from the exercise of existing religious orders past taking vows of farthermost poverty and maintaining an active presence preaching and serving the customs rather than withdrawing into monasteries. Francis of Assisi viewed poverty as a key chemical element of the imitation of Christ who was "poor at birth in the manger, poor every bit he lived in the globe, and naked equally he died on the cantankerous".[27]

The visible public commitment of the Franciscans to poverty provided to the laity a precipitous contrast to the wealth and power of the Church building, provoking "bad-mannered questions".[28]

Early attempts at reform [edit]

Widespread corruption led to calls for reform which called into question the interdependent relationship of Church and State power.[29] Reformers sharply criticised the lavish wealth of churches and the mercenary beliefs of the clergy.[30] For example, reformer Peter Damian labored to remind the Church hierarchy and the laity that dearest of money was the root of much evil.

Usury [edit]

Usury originally was the charging of involvement on loans; this included charging a fee for the employ of money, such as at a bureau de change. In places where interest became adequate, usury was involvement above the rate allowed past law. Today, usury ordinarily is the charging of unreasonable or relatively high rates of interest.

The offset of the scholastics, Saint Anselm of Canterbury, led the shift in thought that labeled charging interest the same as theft. Previously usury had been seen as a lack of charity.

St. Thomas Aquinas, the leading theologian of the Catholic Church building, argued charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to "double charging", charging for both the affair and the employ of the thing.

This did not, as some think, prevent investment. What it stipulated was that in order for the investor to share in the profit he must share the chance. In short he must be a joint-venturer. Simply to invest the coin and expect it to be returned regardless of the success of the venture was to make money simply by having money and non by taking any risk or past doing any work or past any effort or sacrifice at all. This is usury. St Thomas quotes Aristotle as saying that "to live by usury is exceedingly unnatural". St Thomas allows, all the same, charges for actual services provided. Thus a banker or credit-lender could charge for such actual piece of work or endeavour as he did conduct out e.g. any off-white authoritative charges.[ citation needed ]

Reformation [edit]

The rising capitalistic middle class resented the drain of their wealth to the Church; in northern Europe, they supported local reformers against the abuse, rapacity and venality which they viewed as originating in Rome.[31]

Calvinism [edit]

1 schoolhouse of thought attributes Calvinism with setting the stage for the afterward evolution of commercialism in northern Europe. In this view, elements of Calvinism represented a revolt against the medieval condemnation of usury and, implicitly, of profit in general.[ citation needed ] Such a connectedness was advanced in influential works by R. H. Tawney(1880–1962) and by Max Weber (1864–1920).

Calvin criticised the apply of sure passages of scripture invoked by people opposed to the charging of involvement. He reinterpreted some of these passages, and suggested that others of them had been rendered irrelevant by changed weather condition. He too dismissed the argument (based upon the writings of Aristotle) that it is incorrect to charge interest for money because money itself is barren. He said that the walls and the roof of a business firm are barren, also, but it is permissible to charge someone for assuasive him to use them. In the same way, coin can exist fabricated fruitful.[32]

Puritanism [edit]

For Puritans, work was not only arduous drudgery required to sustain life. Joseph Conforti describes the Puritan mental attitude toward work as taking on "the character of a vocation – a calling through which one improved the globe, redeemed time, glorified God, and followed life'due south pilgrimage toward salvation."[33] Gayraud Wilmore characterizes the Puritan social ethic as focused on the "acquisition and proper stewardship of wealth equally outward symbols of God'south favor and the consequent conservancy of the individual."[34] Puritans were urged to be producers rather than consumers and to invest their profits to create more jobs for industrious workers who would thus be enabled to "contribute to a productive gild and a vital, expansive church building." Puritans were counseled to seek sufficient condolement and economic cocky-sufficiency only to avoid the pursuit of luxuries or the accumulation of material wealth for its ain sake.[33]

The rise of commercialism [edit]

In two journal articles published in 1904–05, High german sociologist Max Weber propounded a thesis that Reformed (i.east., Calvinist) Protestantism had engendered the character traits and values that under-girded modernistic capitalism. The English translation of these articles were published in book form in 1930 as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Weber argued that capitalism in northern Europe evolved because the Protestant (peculiarly Calvinist) ethic influenced large numbers of people to appoint in work in the secular globe, developing their own enterprises and engaging in trade and the accumulation of wealth for investment. In other words, the Protestant piece of work ethic was a forcefulness behind an unplanned and uncoordinated mass action that influenced the evolution of commercialism.

Weber'due south work focused scholars on the question of the uniqueness of Western civilisation and the nature of its economic and social development. Scholars have sought to explain the fact that economic growth has been much more rapid in Northern and Western Europe and its overseas offshoots than in other parts of the world including those where the Catholic and Orthodox Churches have been dominant over Protestantism. Some have observed that explosive economic growth occurred at roughly the aforementioned time, or soon after, these areas experienced the rising of Protestant religions. Stanley Engerman asserts that, although some scholars may contend that the 2 phenomena are unrelated, many would observe information technology hard to accept such a thesis.[35]

John Chamberlain wrote that "Christianity tends to atomic number 82 to a capitalistic mode of life whenever siege weather condition do not prevail... [capitalism] is not Christian in and by itself; it is only to say that capitalism is a material by-product of the Mosaic Law."[36]

Rodney Stark propounds the theory that Christian rationality is the primary driver behind the success of capitalism and the Rise of the West.[37]

John B. Cobb argues that the "economism that rules the West and through it much of the East" is straight opposed to traditional Christian doctrine. Cobb invokes the instruction of Jesus that "man cannot serve both God and Mammon (wealth)". He asserts that information technology is obvious that "Western society is organized in the service of wealth" and thus wealth has triumphed over God in the West.[one]

[edit]

Much of Saint Thomas Aquinas'due south theology dealt with issues of social justice.

Social justice mostly refers to the idea of creating a society or institution that is based on the principles of equality and solidarity, that understands and values human being rights, and that recognizes the dignity of every human beingness.[39] The term and modern concept of "social justice" was coined past the Jesuit Luigi Taparelli in 1840 based on the teachings of St. Thomas Aquinas and given further exposure in 1848 by Antonio Rosmini-Serbati.[39] [xl] [41] [42] The idea was elaborated past the moral theologian John A. Ryan, who initiated the concept of a living wage. Father Coughlin also used the term in his publications in the 1930s and the 1940s. It is a function of Catholic social teaching, Social Gospel from Episcopalians and is one of the Four Pillars of the Greenish Party upheld past green parties worldwide. Social justice as a secular concept, distinct from religious teachings, emerged mainly in the late twentieth century, influenced primarily by philosopher John Rawls. Some tenets of social justice take been adopted by those on the left of the political spectrum.

According to Kent Van Til, the view that wealth has been taken from the poor past the rich implies that the redistribution of that wealth is more than a matter of restitution than of theft.[43]

[edit]

Come up on, let united states pray for those who have no piece of work because it is globe tragedy... in these times

Catholic social educational activity is a body of doctrine developed by the Catholic Church building on matters of poverty and wealth, economics, social organization and the role of the country. Its foundations are widely considered[ by whom? ] to have been laid by Pope Leo Xiii'due south 1891 encyclical alphabetic character Rerum novarum, which advocated economic distributism and condemned socialism.

According to Pope Bridegroom XVI, its purpose "is simply to help purify reason and to contribute, hither and now, to the acknowledgment and attainment of what is just.... [The Church building] has to play her part through rational argument and she has to reawaken the spiritual energy without which justice…cannot prevail and prosper",[45] According to Pope John Paul II, its foundation "rests on the threefold cornerstones of human dignity, solidarity and subsidiarity".[46] These concerns repeat elements of Jewish police force and the prophetic books of the Old Attestation, and retrieve the teachings of Jesus Christ recorded in the New Testament, such as his annunciation that "any y'all have done for one of these least brothers of Mine, yous accept done for Me." (Matthew 25:twoscore)

Cosmic social educational activity is distinctive in its consistent critiques of modern social and political ideologies both of the left and of the right: liberalism, communism, socialism, libertarianism, capitalism,[47] Fascism, and Nazism accept all been condemned, at least in their pure forms, by several popes since the late nineteenth century.

Marxism [edit]

Irving Kristol posits that one reason that those who are "experiencing a Christian impulse, an impulse toward the imitatio Christi, would lean toward socialism ... is the mental attitude of Christianity toward the poor. "[17]

Arnold Toynbee characterized Communist ideology as a "Christian heresy" in the sense that it focused on a few elements of the religion to the exclusion of the others.[48] Donald Treadgold interprets Toynbee'due south characterization as applying to Christian attitudes every bit opposed to Christian doctrines.[49] In his volume, "Moral Philosophy", Jacques Maritain echoed Toynbee's perspective, characterizing the teachings of Karl Marx as a "Christian heresy".[50] After reading Maritain, Martin Luther King, Jr. commented that Marxism had arisen in response to "a Christian world unfaithful to its ain principles." Although King criticized the Soviet Marxist–Leninist Communist government sharply, he yet commented that Marx'south devotion to a classless society made him almost Christian. Tragically, said King, Communist regimes created "new classes and a new lexicon of injustice."[51]

[edit]

Christian socialism generally refers to those on the Christian left whose politics are both Christian and socialist and who see these 2 philosophies as being interrelated. This category tin include Liberation theology and the doctrine of the social gospel.

The Rerum novarum encyclical of Leo 13 (1891) was the starting point of a Cosmic doctrine on social questions that has been expanded and updated over the course of the 20th century. Despite the introduction of social thought as an object of religious thought, Rerum novarum explicitly rejects what it calls "the master tenet of socialism":

"Hence, information technology is clear that the primary tenet of socialism, community of goods, must be utterly rejected, since information technology merely injures those whom it would seem meant to benefit, is directly contrary to the natural rights of mankind, and would introduce confusion and disorder into the commonwealth. The first and most cardinal principle, therefore, if 1 would undertake to alleviate the condition of the masses, must be the inviolability of private property." Rerum novarum, paragraph 16.

The encyclical promotes a kind of corporatism based on social solidarity among the classes with respects for the needs and rights of all.

In the November 1914 issue of The Christian Socialist, Episcopal bishop Franklin Spencer Spalding of Utah, U.S.A. stated:

"The Christian Church exists for the sole purpose of saving the man race. Then far she has failed, but I think that Socialism shows her how she may succeed. Information technology insists that men cannot be fabricated right until the cloth conditions be made correct. Although man cannot live by staff of life alone, he must have bread. Therefore, the Church must destroy a system of gild which inevitably creates and perpetuates unequal and unfair weather of life. These unequal and unfair conditions accept been created by competition. Therefore, contest must finish and cooperation accept its place."[52]

Despite the explicit rejection of Socialism, in the more than Cosmic countries of Europe the encyclical's teaching was the inspiration that led to the formation of new Christian-inspired Socialist parties. A number of Christian socialist movements and political parties throughout the world group themselves into the International League of Religious Socialists. It has member organizations in 21 countries representing 200,000 members.

Christian socialists draw parallels between what some have characterized equally the egalitarian and anti-institution message of Jesus, who–co-ordinate to the Gospel–spoke against the religious authorities of his time, and the egalitarian, anti-establishment, and sometimes anti-clerical message of most gimmicky socialisms. Some Christian Socialists accept become active Communists. This phenomenon was nearly mutual amidst missionaries in China, the most notable being James Gareth Endicott, who became supportive of the struggle of the Communist Party of Red china in the 1930s and 1940s.

Michael Moore'south film Capitalism: A Love Story also features a religious component where Moore examines whether or not capitalism is a sin and whether Jesus would be a capitalist,[53] in order to smooth lite on the ideological contradictions among evangelical conservatives who support free market ideals.

Liberation theology [edit]

Liberation theology[54] is a Christian movement in political theology which interprets the teachings of Jesus Christ in terms of a liberation from unjust economical, political, or social conditions. It has been described by proponents as "an interpretation of Christian faith through the poor'southward suffering, their struggle and hope, and a critique of society and the Catholic religion and Christianity through the eyes of the poor",[55] and past detractors as Christianized Marxism.[56] Although liberation theology has grown into an international and inter-denominational move, it began every bit a movement within the Roman Catholic Church in Latin America in the 1950s–1960s. Liberation theology arose principally equally a moral reaction to the poverty acquired past social injustice in that region. The term was coined in 1971 by the Peruvian priest Gustavo Gutiérrez, who wrote 1 of the move's near famous books, A Theology of Liberation. Other noted exponents are Leonardo Boff of Brazil, Jon Sobrino of Republic of el salvador, and Juan Luis Segundo of Uruguay.[57] [58] Saint Óscar Romero, old Archbishop of San Salvador, was a prominent exponent of liberation theology, and was assassinated in 1980, during the Salvadoran Ceremonious State of war; he was canonized equally a saint by Pope Francis in 2018.[59]

The influence of liberation theology within the Catholic Church macerated subsequently proponents using Marxist concepts were admonished past the Vatican's Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) in 1984 and 1986. The Vatican criticized certain strains of liberation theology – without actually identifying any detail strain – for focusing on institutional dimensions of sin to the exclusion of the private; and for allegedly misidentifying the Church hierarchy as members of the privileged class.[sixty]

Run across too [edit]

- Jesus and the rich boyfriend

- Parable of the Rich Fool

- Unproblematic living

- United Social club

References [edit]

- ^ a b Cobb, Jr., John B. "Eastern View of Economic science". Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved 2011-04-x .

- ^ Mahoney, Jack (1995). Companion encyclopedia of theology. Taylor & Francis. p. 759.

- ^ Liacopulos, George P. (2007). Church building and Society: Orthodox Christian Perspectives, Past Experiences, and Modern Challenges. Somerset Hall Press. p. 88. ISBN9780977461059.

- ^ a b c d Miller, David W. (April 2007). "Wealth Creation equally Integrated with Religion: A Protestant Reflection". Muslim, Christian, and Jewish Views on the Creation of Wealth; April 23–24, 2007.

- ^ a b c Kahan, Alan S. (2009). Mind vs. money: the state of war betwixt intellectuals and commercialism. Transaction Publishers. p. 43. ISBN9781412828772.

- ^ Wells, Samuel; Quash, Ben (2010). Introducing Christian Ethics . John Wiley and Sons. p. 244. ISBN9781405152778.

Christian land wealth usury.

- ^ "Homily of His Holiness Benedict Xvi". Vatica.va. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 31 Jan 2022.

- ^ Dorothy Day (February 1945). "More About Holy Poverty. Which Is Voluntary Poverty". The Catholic Worker. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ Cornell, Tom; Ellsberg, Robert (1995). A Penny a Copy: Readings from the Cosmic Worker. Orbis Books. p. 198.

At its deepest level voluntary poverty is a way of seeing the globe and the things of the globe.… The Gospels are quite articulate: the rich man is told to sell all he has and give to the poor, for it is easier for a camel to laissez passer through the eye of a needle than for a rich human to enter heaven. And we are clearly instructed that 'yous tin not serve God and Mammon'.

- ^ Fahlbusch, Erwin (2005). The Encyclopedia Of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 307. ISBN978-0-8028-2416-v . Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- ^ a b Perrotta, Cosimo (2004). Consumption every bit an Investment: The fear of goods from Hesiod to Adam Smith. Psychology Printing. p. 43. ISBN9780203694572.

- ^ a b c Perrotta, Cosimo (2004). Consumption as an Investment: The fear of appurtenances from Hesiod to Adam Smith. Psychology Press. p. 44. ISBN9780203694572.

- ^ Kelly, Joseph Francis (1997). The World of the early Christians . Liturgical Press. p. 166. ISBN9780814653135.

Former Testament attitudes poverty wealth.

- ^ Frederick, Robert (2002). A companion to business organization ethics. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 292–93. ISBN9781405101028.

- ^ a b c Kahan, Alan Due south. (2009). Mind vs. money: the war betwixt intellectuals and capitalism. Transaction Publishers. p. 44. ISBN9781412828772.

- ^ a b Kahan, Alan S. (2009). Heed vs. money: the war between intellectuals and capitalism. Transaction Publishers. p. 42. ISBN9781412828772.

- ^ a b Kristol, Irving (1995). Neoconservatism: the autobiography of an idea. Simon and Schuster. p. 437. ISBN9780028740218.

- ^ Ely, Richard Theodore; Adams, Thomas Sewall; Lorenz, Max Otto; Young, Allyn Abbott (1920). Outlines of economic science. Macmillan. p. 743.

Christian fathers attitudes coin wealth.

- ^ a b Grant, Robert McQueen (2004). Augustus to Constantine: the ascent and triumph of Christianity in the Roman world. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 49. ISBN9780664227722.

- ^ Rothbard, Murray N. (2006). An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. Ludwig von Mises Institute. p. 33. ISBN9781610164771.

Christian fathers attitudes coin wealth.

- ^ Hunt, E. K. (2002). Holding and Prophets: The Evolution of Economical Institutions and Ideologies. Thou.E. Sharpe. p. 10. ISBN9780765632715.

- ^ Greyness, Madeleine (2003). The Protestant Reformation: belief, practice, and tradition. Sussex Academic Press. p. 119. ISBN9781903900116.

- ^ Kahan, Alan South. (2009). Mind vs. money: the state of war between intellectuals and capitalism. Transaction Publishers. p. 46. ISBN9781412828772.

- ^ Bishko, Charles Julian (1948). "The Date and Nature of the Spanish Consensoria Monachorum". The American Journal of Philology. 69 (four): 377–395. doi:ten.2307/290910. JSTOR 290910. also at [1]

- ^ Topographies of power in the early on Centre Ages by Frans Theuws, Mayke de Jong, Carine van Rhijn 2001 ISBN 90-04-11734-2 p. 357

- ^ Bartlett, Robert (2001). Medieval panorama. Getty Publications. p. 56. ISBN9780892366422.

- ^ The Word made flesh: a history of Christian idea by Margaret Ruth Miles 2004 ISBN 978-1-4051-0846-ane pp. 160–61

- ^ William Carl Placher (15 Apr 1988). Readings in the History of Christian Theology: From its beginnings to the eve of the Reformation. Westminster John Knox Printing. pp. 144–. ISBN978-0-664-24057-8 . Retrieved eleven Oct 2011.

- ^ Placher, William Carl (1988). Readings in the History of Christian Theology: From its ancestry to the eve of the Reformation. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 144. ISBN9780664240578.

- ^ Porterfield, Amanda (2005). Healing in the history of Christianity. Oxford University Press US. p. 81. ISBN9780198035749.

- ^ Herrick, Cheesman Abiah (1917). History of commerce and industry. Macmillan Co. p. 95.

medieval Europe Christian Church wealth.

- ^ Calvin's position is expressed in a letter to a friend quoted in Le Van Baumer, Franklin, ed. (1978). Main Currents of Western Idea: Readings in Western Europe Intellectual History from the Middle Ages to the Present. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN0-300-02233-six.

- ^ a b Conforti, Joseph A. (2006). Saints and strangers: New England in British North America. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 42. ISBN9780801882531.

- ^ Wilmore, Gayraud S. (1989). African American religious studies: an interdisciplinary anthology . Knuckles University Press. p. 12. ISBN0822309262.

Puritan Stewardship of wealth.

- ^ Engerman, Stanley L. (2000-02-29). "The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism". Archived from the original on 2011-03-07. Retrieved 2011-04-10 .

- ^ Chamberlain, John (1976). The Roots of Capitalism.

- ^ Stark, Rodney (2005). The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success. New York: Random House. ISBN1-4000-6228-iv.

- ^ a b Butts, Janie B.; Rich, Karen (2005). Nursing ideals: across the curriculum and into practice . Jones and Bartlett Publishers. ISBN978-0-7637-4735-0.

Nursing ideals Butts Rich Jones.

- ^ Battlefield criminal justice past Gregg Barak, Greenwood publishing group 2007, ISBN 978-0-313-34040-6

- ^ Engineering and Social Justice By Donna Riley, Morgan and Claypool Publishers 2008, ISBN 978-i-59829-626-6

- ^ Spirituality, social justice, and language learning By David I. Smith, Terry A. Osborn, Information Age Publishing 2007, ISBN i-59311-599-7

- ^ Galston, William A.; Hoffenberg, Peter H. (2010). Poverty and Morality: Religious and Secular Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 72. ISBN9781139491068.

- ^ SkyTg24

- ^ (Pope Benedict XVI, Deus Caritas Est, 28).

- ^ (John Paul II, 1999 Churchly Exhortation, Ecclesia in America, 55).

- ^ Quadragesimo anno, § 99 ff

- ^ Toynbee, Arnold (1961). A Study of History. p. 545.

The Communist ideology was a Christian heresy in the sense that it had singled out several elements in Christianity and had concentrated on these to the exclusion of the residue. Information technology had taken from Christianity its social ethics, its intolerance and its fervour.

- ^ Treadgold, Donald Due west. (1973). The Westward in Russian federation and China: Russia, 1472–1917 . Cambridge University Press. p. 256. ISBN9780521097253.

Arnold Toynbee Communism Christian heresy.

- ^ Maritain, Jacques. Moral Philosophy.

This is to say that Marx is a heretic of the Judeo-Christian tradition, and that Marxism is a 'Christian heresy', the latest Christian heresy

- ^ From civil rights to human rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the struggle for economic justice . Academy of Pennsylvania Press. 2007. p. 42. ISBN9780812239690.

Martin Luther Male monarch poverty wealth.

- ^ Berman, David (2007). Radicalism in the Mountain West 1890–1920. University Printing of Colorado. pp. 11–12.

- ^ Moore, Michael (October 4, 2009). "For Those of You on Your Way to Church This Morning ..." The Huffington Post . Retrieved May 3, 2010.

- ^ In the mass media, 'Liberation Theology' tin sometimes be used loosely, to refer to a wide variety of activist Christian thought. In this article the term will be used in the narrow sense outlined hither.

- ^ Berryman, Phillip, Liberation Theology: essential facts nigh the revolutionary motion in Latin America and beyond(1987)

- ^ "[David] Horowitz starting time describes liberation theology equally 'a course of Marxised Christianity,' which has validity despite the awkward phrasing, only then he calls it a form of 'Marxist–Leninist credo,' which is simply not true for most liberation theology..." Robert Shaffer, "Acceptable Bounds of Bookish Discourse Archived 2013-09-04 at the Wayback Machine," Organization of American Historians Newsletter 35, Nov, 2007. URL retrieved 12 July 2010.

- ^ Richard P. McBrien,Catholicism(Harper Collins, 1994), affiliate IV.

- ^ Gustavo Gutierrez,A Theology of Liberation, First (Spanish) edition published in Lima, Peru, 1971; first English language edition published by Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York), 1973.

- ^ Zraick, Karen (October 13, 2018). "Óscar Romero, Archbishop Killed While Maxim Mass, Will Be Named a Saint on Dominicus". The New York Times . Retrieved Apr 27, 2021.

- ^ Wojda, Paul J., "Liberation theology", in R.P. McBrien, ed., The Catholic Encyclopedia (Harper Collins, 1995).

Further reading [edit]

- Clouse, Robert G.; Diehl, William E. (1984). Wealth & poverty: four Christian views of economics. InterVarsity Press.

- Wheeler, Sondra Ely (1995). Wealth as peril and obligation: the New Attestation on possessions. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

- Perrotta, Cosimo (2004). Consumption as an Investment: The fear of goods from Hesiod to Adam Smith. Psychology Printing.

- Holman, Susan R. (2008). Wealth and poverty in early Church and society. Bakery Bookish.

- Kahan, Alan South. (2009). Mind vs. coin: the war between intellectuals and capitalism. Transaction Publishers.

- Neil, Bronwen; Allen, Pauline; Mayer, Wendy (2009). Preaching poverty in Belatedly Antiquity: perceptions and realities. Evangelische Verlagsanstalt.

External links [edit]

- Does God Desire You To Be Rich?

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Christian_views_on_poverty_and_wealth

0 Response to "What Factor Might Influence Family Composition? Religious Beliefs Poverty War All of the Above"

Post a Comment